Growing up a biracial child in the Bronx, New York and primarily receiving my dance and academic education in Manhattan, I sincerely believed I was living in a post-racial world. I felt privileged to live in a big house with a yard, pets, two parents (in my early years) and I always had dance. I’d laugh thinking that suburban people were the ones “living under a rock”, but it wasn’t until I toured the country as a professional dancer that I realized, America was not New York. Living in a salad bowl of culture, race, language and (relatively) efficient public transportation, was the boulder that shadowed me from understanding the deep seated racism that oozes out of every pore of our nation. America is strip malls and confederate flags. It is gentrification and segregated neighborhoods. It’s tyranny masked in democracy and greed overpowering ethics. It’s the Eurocentric world of ballet. Yes, its topography can be exquisite and there is beauty and opportunity at arms’ length, but at heart it is a nation divided by the oppressed and their oppressors. I didn’t understand the complex structures of institutionalized racism until I was a young adult, and I was deeply saddened to realize that racism had dictated so many aspects of my life without even knowing it. Dance was no exception.

From first through fifth grade I attended P.S.24, a public school in Riverdale, New York. It never occurred to me why my Italian- American mother didn’t want my older sister and me to attend a public school in my own neighborhood of the Bronx. My classmates at P.S. 24 were incredibly diverse and I was friends with kids from all walks of the earth. Excluding the gym teacher and my fifth grade teacher, every other instructor I had was white. I didn’t question it. I didn’t question why the ESL (English as a 2nd language) students were in the same class as students with learning disabilities. I was young and unaware and I loved school and thrived in the academic environment. I began an after school dance program at Ballet Tech in fourth and fifth grade. Minority students were picked up on a bus from their schools in various boroughs and we were driven to Manhattan to take dance lessons. I never thought of myself as disenfranchised, only very lucky. As a young dance student at the Bronx Dance Theatre, Ballet Tech and later the Dance Theatre of Harlem, I was primarily in classrooms with other black and brown kids. After fifth grade I was expected to attend the attached middle school M.S. 141, as my older sister had. By the time I was ready to graduate, the Riverdale school board had changed the zoning laws and I was no longer entitled to attend the middle school. Covert racism at its finest. In the scramble of trying to find a school to attend in the middle of summer, I ended up at the Professional Performing Arts School in Midtown. My mother shielded me from the reality of this adjustment and I was just thankful that my world was opening up to more dance in “THE BIG CITY.”

While at the Professional Performing Arts School I continued to dance afterschool at the School of American Ballet and in the summers at the Dance Theatre of Harlem. I was accepted to the School of American Ballet through their inaugural community audition in 1998. These were free auditions for children in the outer boroughs, and I auditioned in the ripped brown tights I wore at the Dance Theatre of Harlem. In the very early years, both at SAB and PPAS, my surroundings remained relatively diverse. Even though I was in a performing arts school on 48th Street, we were a very ethnically mixed group of students. Most of my teachers were white but my education was very progressive; I remember reading The Middle Passage in sixth grade, to my mother’s dismay, but perhaps secret delight. In the children divisions at SAB I was not the only racially diverse dancer, though we were still in the minority. Through eighth grade I received my dance education at both SAB and DTH. When I started high school at LaGuardia H.S. for the Performing Arts, I solely began to train at SAB during the year.

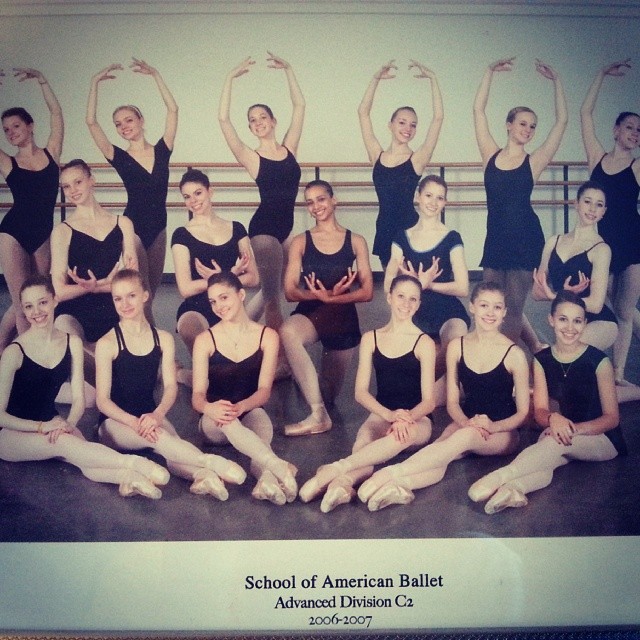

Throughout my time at the School of American Ballet, I was always one of three, or one of two, and in the later years, the only black woman in the upper division. During my tenure there was only one black female dancer in the New York City Ballet, Aesha Ash. When she left in the early 2000’s, there were none. She was, and is, one of my first role models and I found it deeply troubling that there was absolutely no female representation of diversity in the company for many years after she left. While at the School of American Ballet I never really felt ostracized for not being white. I was tall for my age and had a lot of great opportunities, performing with the NYCB many times as a kid, and I think I was generally liked. It didn’t really hit me until I became a young adult how very disturbing the situation was. The socio-economic divide became more evident as years went by. The economic burden of the incredulous tuition on my now single mother was extreme. Peers were being picked up by chauffeurs and I would wait with the black security guard, Carlton, until my mother could pick me up after work. The only real diversity I saw in the entire institution were the chefs in the cafeteria and the security workers. The school later launched their first diversity initiative in 2012. When I was in the advanced level and our uniform was a white leotard and pink tights, I was the only student in my class who was asked to not wear a ballet skirt. I was extremely embarrassed because I was at an age where I was going through puberty and quite honestly, one of the only girls in my class with a round ass. I was ashamed when that same instructor asked me publicly what my plans were for college, and no one else. She also called me by the wrong name for half a year. I was the only black student in my level. I was resentful and questioned whether these actions were racially driven. Despite all the privilege I had, this was just a thought that my white peers would never have to consider.

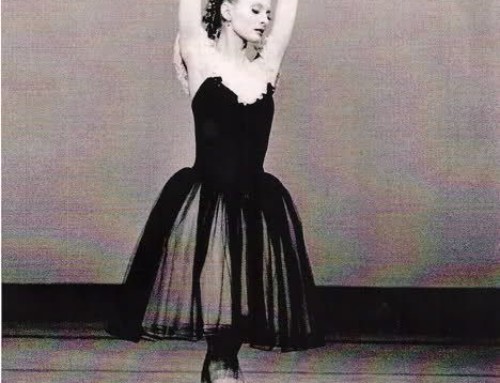

Aesha Ash

I attended Juilliard after leaving SAB and I was told we had a relatively diverse class, five out of 24 of us were black. I was initially waitlisted, but ironically I took the place of another biracial female. I can’t tell if the issues I had in college were because I was black, but I do know that other black students shared my experiences. I entered Juilliard on the honor roll and graduated with a noticeably lower G.P.A, all because of grades I received in dance. I had three black teachers while I was there, between my dance division and academic courses combined. I worked with only one male choreographer of color during the entire four years. I was placed on probation my junior year ostensibly for “bad posture”, even though I was talented, attentive, eager, had good attendance, great behavior and a positive relationship with my teachers. I was given three months to “correct” this, or my place at the school would be compromised. My time there was incredibly tumultuous. Through the self-hatred I built up from never really feeling good enough, I also learned a great deal about myself. Ultimately I’m glad I got my B.F.A. degree and graduated knowing I was prepared for the professional world of dance, regardless of what might be thrown at me.

After graduating from Juilliard I danced professionally with the Dance Theatre of Harlem for two and a half seasons, and then moved to Salt Lake City, Utah to join Ballet West. The micro-aggressions I’ve encountered during my six years in Utah are extremely perplexing and burdensome. Although I had experienced the backhanded sting of racism in New York, I always had a community of multi-racial friends in which to relate and unload. In Utah, in a population of about 2% African-Americans, many times I felt utterly alone. There are two black female dancers in the company and I can’t tell you the amount of times I’ve been called her name and complimented for her work. During one of my first encounters with our marketing team I was referred to as “An ethnic”, and chosen for the project because “An ethnic would be great to represent the company”. I’ve had to pancake the straps of all of my own costumes. I’ve been photo-credited as the black male dancer in the company. I’ve only participated in one black history month celebration in six years, and I had to ask to be included. We have performed one barefoot modern dance piece during my time here. That piece was the only repertoire, other than Nutcracker, to prominently feature every dancer of color in the company. Outside the studio, I’ve only seen two people of color working in the entire building, in both the administrative and artistic positions. I’ve been asked “Can I touch your hair?” and “How often do you wash your hair?” by co-workers many times. A friend’s parent asked if I knew who my father was, and I’ve verbally argued with a white man in a bar who insisted I was from Ethiopia, because he had extensively researched the Ethiopian culture. In a racial sensitivity meeting a co-worker expressed that racism against black people was the current fad. I’ve bitten my tongue time and time again, and been so angry at myself for not speaking up. But as James Baldwin said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Ballet West dancers in Balanchine’s ‘Square Dance’ (above) & Cunningham’s ‘Summerspace’ (below)

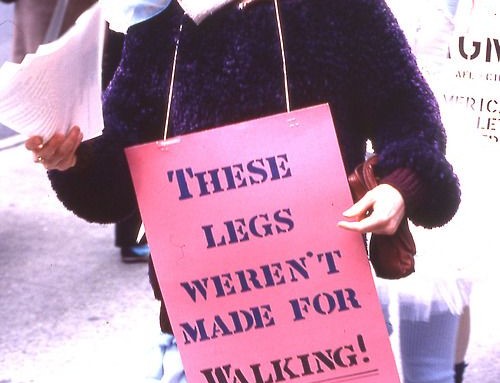

The dance world, and more specifically ballet, is a dichotomous environment of Eurocentric values, elitism and poor starving artists. The training at renowned institutions is ridiculously expensive. I was accepted into advanced levels of highly-respected summer intensives, but had to turn them down year after year. My mother couldn’t afford the tuition, even though she had a steady middle class income as an educator. The economic costs immediately inhibit large populations of color. I wonder how many lower to middle class students were filling the halls of the School of American of Ballet before they created a free community audition. I can only imagine those halls were even more homogenous than when I attended. All of the tools you need to succeed in ballet are expensive: the clothing, the pointe shoes, private lessons, the training. Everything about these elite institutions is structured to exclude black and brown communities, from income disparity, to lack of exposure, to lack of representation. In 2017, Gaynor Minden was the first major retailer to create brown pointe shoes, followed by Freed and most recently Grishko, in 2020. Ballet has been around for nearly 200 years, and brown pointe shoes arrived on the scene three years ago. To date, major ballet companies still perform in black face. The vast majority of artistic directors and executive directors are white males. The history and legacy of black dancers has been heavily erased. Schools remain predominantly white and consequently, stages do as well. Corps de ballets of major companies around the world have few to no dancers of color because of the Eurocentric classical aesthetic. High ticket prices and lack of exposure exclude vast audiences of color. Low salaries for professional dancers inhibit many who are not financially stable from pursuing a career. Artistic directors attend International conferences to increase inclusion, and yet still only have one or two dancers of color in their ranks. They don’t hire choreographers of different backgrounds to create work, and consequently the same stories are being told. Progress has been made and yet so many facets of the ballet world continue to scream to black artists, YOU DO NOT BELONG.

I’m indebted to my mother for every sacrifice she made to support my dreams. I feel extremely lucky to have had the opportunities and exposure I did, but I can’t help but wonder if my journey would have been different had I had two black parents….or two white ones.

This is an outstanding article. You need to consider writing a book.

Thank you!

And I want to pre-order that book!

haha thank you!

I really relate to this article. I remember people saying black dancers are more attracted to “modern” dance than “ballet” and me wanting to yell it’s because you don’t welcome us!!!!!!

Exactly. Part of the inspiration for American modern dance in the first place.

Dear Gabrielle,

My claim to fame is that Tesha McCord is the older of my two daughters.

That said—I am writing to congratulate you the amazing story that you have shared.

Without a doubt, you are an extremely talented writer.

In fact, I dare say that I feel safe to offer you my personal 5 star assessment for your classical ballet talents.

Congratulations To You Ms Gabrielle Salvatto.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️👍🏾⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

This is a very moving testimony, and a sad one. You are one of my favorite dancers in the BW company, and I’m always thrilled when I see your name on the program, disappointed when I only get to glimpse you in the corps. You make a fantastic point about all the barriers that need to be addressed if ballet wants to remain relevant beyond just an elite, white sphere as we go forward; the work of building diverse audiences as well as companies should not have to fall exclusively on Dance Theater of Harlem, Alvin Ailey, and a few others. Thank you for the courage of your voice and your commitment to the art form.

Thank you so much ! I really appreciate it. Hope you are safe and well.

[…] Gabrielle Salvatto: Black Faces in White Spaces […]

[…] Gabrielle Salvatto: Black Faces in White Spaces […]

Hi Gabrielle. My name is Peter Valdes.

My daughter Adriana went to Ballet Hispánico and SAB with you.

Your article is spot on! You’re a great writer! It pains me that you went through this journey. But, I see it has not prevented you from becoming a great woman and person. Please say hello to your great Mom!

Thank you so much Peter! I hope you and your family are doing well. Much love to you all!!

[…] Black Face in White Spaces, Interview En L’Air Gabrielle Salvatto, NYC Dance Project Beyond Solidarity Statements: The Real Work Ballet Organizations Must Do to Dismantle Systemic Racism, Pointe Magazine […]

j8dmcz

4ahee3

o4olza

pin-up casino giris: pin up az?rbaycan – pin up onlayn kazino

http://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican pharmacy – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmacy online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

http://northern-doctors.org/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmacy – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican pharmacy – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican rx online: mexican pharmacy – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://northern-doctors.org/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico: northern doctors pharmacy – mexico pharmacy

https://northern-doctors.org/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: northern doctors pharmacy – mexican drugstore online

mexican mail order pharmacies: northern doctors – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

http://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacy

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican pharmacy online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://northern-doctors.org/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican northern doctors – mexican drugstore online

http://northern-doctors.org/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://northern-doctors.org/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

https://northern-doctors.org/# medication from mexico pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – mexican pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

https://northern-doctors.org/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: northern doctors – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://northern-doctors.org/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican northern doctors – reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican pharmacy

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: northern doctors – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican northern doctors – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://northern-doctors.org/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: northern doctors – mexican rx online

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican mail order pharmacies

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican mail order pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican pharmacy online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican pharmacy northern doctors – mexican drugstore online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: Mexico pharmacy that ship to usa – buying from online mexican pharmacy

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexican drugstore online

https://northern-doctors.org/# medication from mexico pharmacy

https://northern-doctors.org/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://cmqpharma.online/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=http://cmqpharma.com/#]cmq mexican pharmacy online[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican rx online [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]online mexican pharmacy[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]mexican online pharmacy[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican rx online: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican mail order pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies [url=http://cmqpharma.com/#]pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa[/url] mexican rx online

mexican rx online [url=http://cmqpharma.com/#]online mexican pharmacy[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]buying prescription drugs in mexico online[/url] medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online [url=https://cmqpharma.online/#]mexican pharmacy online[/url] mexican pharmacy