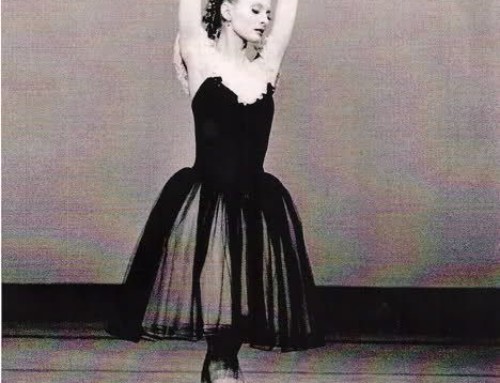

As a biracial girl growing up in the Bronx, diversity was a large part of my everyday life. Inside my household, the cuisine I ate, my neighborhood, the subway rides to the city, the public school system…it was an array of color and culture. My mother taught my sister and me to be accepting of everyone, to be proud of who we were and to be understanding of all that was different. At the onset of my professional studies, and later in my career as a ‘black ballerina’, diversity became like a dark cloud that followed me everywhere, often threatening to burst into storm. It seemed to strip me of my identity as an Italian/African-American dancer, and transform me into an ambassador for minorities struggling to find their place in a world that inherently rejects them.

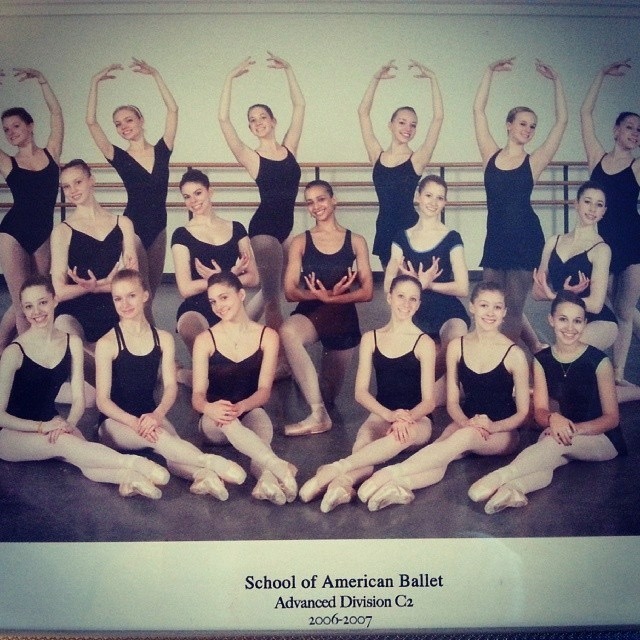

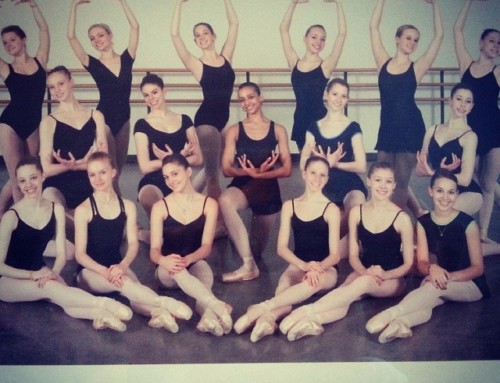

Despite having trained most of my life at the School of American Ballet, one of the ‘whitest’ and most affluent schools in New York, it never occurred to me that I would be looked upon as different, or had more to prove than my fellow classmates. Ballet is extremely competitive, and perfecting the rigorous technique required of a ballerina seemed to be a united struggle of survival of the fittest (no pun intended). The only personal setbacks that differentiated me from my peers existed because my single mother had to pay the outrageous tuition on her own, and maybe that my butt was slightly larger than most of the girls in the room. Until I entered high school, I was also attending the Dance Theatre of Harlem on some weekends and during the summers. In my experience, both DTH and SAB were prestigious institutions where students of different colors and shapes were treated the same, and received equal criticism and praise from their teachers. Whatever gossip and speculation occurred, at either program, seemed to mostly circulate through the parents, and my mother made it a point to stay far away from it.

When I joined the Juilliard class of 2011, “diversity” was the last thing on my mind. During our first 19th floor dorm meeting, I was surrounded by international students, brown students, white students, biracial kids…an assortment of multi-ethnic individuals all enrolled there to focus on, and perfect their craft. I thought surely that Juilliard only required talent for acceptance, and as a private (extremely expensive) institution, would be unaffected by the need to fill any sort of “quota” for diversity’s sake. There was the Black Student Union, a Korean Christian Community, and plenty of other options and opportunities to find your niche. I felt that we were a united minority; a group of young artists seeking a forum of expression and living in an age where the majority of people didn’t consider being a professional dancer a ‘real job.’ In my four years at Juilliard I never felt that I was subjected to any sort of discrimination or unique judgement, (well, at least not because of my race) but during my Freshman year I was called in to my first “black student meeting.” All of the black students in the dance department were asked there to openly and comfortably discuss any personal incidents in which they may have felt slighted by the community for being a minority. The two women who spear-headed the discussion were the only two African- American administrators when they joined the staff. They explained that when they first started working at the school they were discouraged from even walking down the hallway together, lest someone thought they were conspiring together in their “blackness”. I’m sure at that time the struggles they faced were very real and unjust, but here we were in 2007 stirring up the pot of racial injustice where I thought none had existed. All of us sitting in that meeting had come from various backgrounds and circumstances, and I would never negate or undermine the experiences of my colleagues and friends. I just felt that being all inclusive in this way forced me to feel differently about myself. Now I wondered if that was how I was viewed by everyone else who wasn’t in that room.

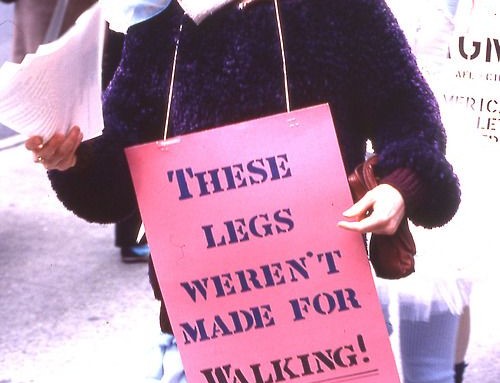

I am not oblivious; it’s always been obvious to me that there were fewer students of color in all of the dance programs I attended. It would be naïve to ignore the apparent reality of racial inequality in classical ballet, especially for women. These days you can’t miss the outpouring of articles and social media threads that discuss and question the various reasons why there is a lack of “black swans” in academies and major companies. The rift expands beyond the stage; the lack of diversity is currently a much discussed issue in Hollywood and in large business corporations. Thanks to outspoken journalists and social media, through groups like Brown Girls Do Ballet, programs like Project Plie, and the success and exposure of Misty Copeland’s story, we have made leaps and bounds in ‘diversifying’ the world of classical ballet. Now we have to push past the current generic understanding that diversity just means one or two. We have to create an environment where ‘black student meetings’ and ‘brown girls only’ auditions are not what’s necessary to make ballet more colorful. We must find a way to lift the burden of skin color off any young artist who is too afraid to pursue her dreams because of it. And narrow the socio-economic gap, providing equal scholarship opportunities to female dance students, so that they can have the means to do so. Diversity…how about equality? My pointe exactly!

“..it feels like medicine ‘Diversity’ is like, ‘Ugh, I have to do diversity’…I recognize and celebrate what it is, but that word, to me, is a disconnect. There’s an emotional disconnect. ‘Inclusion feels closer; ‘belonging’ is even closer”.

NYTimes Magazine. ‘Variety Show’ by Anna Holmes

Very well said Gabi. I feel you.

So important – and so elegantly put Gabi. You write beautifully.

Interesting and enlightening perspective Gabi. You make your mom proud.

Brava Gabi. Beautifully said. I am so proud of you for so many reasons. Let us toast to the day when diversity is the norn and celebrated for the statement of richness and beauty it makes for all of humanity. I love you dearly!

Gabi your ‘pointe’ is valid and your voice is necessary. While Brown Girls Do Ballet’s “public” goal is celebrate diversity in ballet, it’s private goal is to be able to level the playing field for girls who might not be able to afford ballet and to expose young girls who know nothing of ballet to it thru beautiful images such as yours. Your voice is what’s needed as someone in the trenches who has seen all sides of the diversity push. Please keep writing sharing your insight.

Thank you so much! I’m a huge fan on Brown Girls Do Ballet and know that social media has brought a lot more attention and light to the uncomfortable discussion of ‘diversity’

Gabi dear… yours is one of the most intelligent, and heartfelt, descriptions of the long, baby-step journey toward acceptance. Resistance, as you well know, has been fierce.

As a kid in the 1940s’ Bronx, my best friend “Ducker”, a black girl, had to sit in the back of the bus. So, I sat with her. Lotsa bad looks and nasty comments … and I knew how much it hurt her. “whites only” signs were all over the place …

so it became a two-way street: I wanted to go to Ducker’s church, but couldn’t because I’m white. Well, Italian. The singing at her church was awesome … and people actually seemed happy to be there: amazing. So I walked to church with her and her family, and then lay on the ground by the basement window so I could hear what was doing. I believed that when I was older, all that bad shit would have ended.

Man, a fucking way harder, LONGER fight than expected. White people forget that upon arrival here, they were the minority. Look how nicely they “corrected” that!

Yours is an apparent, and very difficult, victory over frightened tiny minds, as well as a personal professional victory for you and your dear Momma!! Females bring to life EVERY person who ever lived. Strong females like you and your Mom then have to fight in brutal baby-steps for themselves …which in turn helps others.

Whenever ya are read this, kindly get off your slightly-larger butt to take a well-deserved bow 🙂

Love from cuz Natalie