Can you give, dare I say, a generic explanation for someone who doesn’t really know what Kwanza is?

Initially, it was founded by Dr. Maulana Ron Karenga in 1966. Black people were searching for and continue to search for our roots, our cultural identity that oftentimes living within the Western society that we live in and we’ve been raised in, and because many of us are the products of an event that happened in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, you know, that displaced us from the continent and we’ve ended up living throughout the African Diaspora, all throughout the world. I’m talking, of course, about the Middle Passage and slavery. So when that loss of language and spirituality and culture and roots and all of the things, that means something for us.

Kwanza would go on to connect African American people with their historical past with their cultural past, with their spiritual pasts and that it centered in the roots of traditions and practices that exist within the continent. And so if we empower ourselves with values that strengthen that sense of community and family, by extension we end up extending those values and strengthening those systems of practice in the larger community and the nation at large.

I think it’s important to emphasize that Kwanza was created for African Americans in order to give us, not an alternative to replace Christmas, because you can continue to still practice Christmas or whatever you celebrate, a non religious, non heroic and non-historic celebration. But it is definitely cultural and the importance of culture is that it is a living entity.

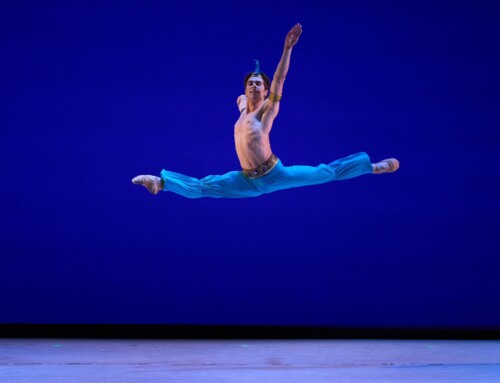

How do you approach blending various dance styles?

I’m an African American. In my studies, I had just as much Ballet and Limon and Horton, Graham too. I should say, I didn’t do very well for Graham because of my hip sockets. As a director and choreographer, you pull upon all those experiences. You know, I don’t love African dance, more then I love Ballet, or more than I love Modern or more than I love in recent years, hip hop, or any more of the other expressions of movement.

What I decided to create, reflected my training, so yes, I had Baba Chuck Davis as my African dance father, but my dance mother was mama Joan Miller, a former dancer of Eleo Pomare and Jose Limon.

Dance is a physical language. It has rhythm in it. And with that rhythm in those codified forms of movement, it’s the ways and means to communicate and talk about things which are important to this, whether they are artistic and they CAN be just artistic. I use any and every movement at my disposal to tell these my stories

Photo from njpac.org

What are some of the most significant challenges you face, not only in creating, but in directing?

I am going to be 73 next week and and I have been laser focused since I started dance.

I came to dance late, and I was in music most my life. I don’t know what kind of musician I was supposed to be. I grew up backstage at the Apollo because my grandfather used to tour with Duke and Ella. So, I got all of that energy by sitting on the foot of the stage backstage and watching performances. As a child, I toured with my father in what they call the Chitlin Circuit, you know, not the big circuit. Those experiences empowered me.

My father said, “Whatever you choose, don’t choose dance, because it’s the one that pays the least. And, you know, with the talent that you have, if you apply that talent to music and film and theater, you’ll probably be much wealthier. But you must follow your heart. So, choose what you what you believe in”. So, I chose dance, and I’ve been laser focused. So, when you talk about the challenges, I didn’t see the obstacles. I was driven.

For me coming up within the movements, the civil rights movement, the black power movement, the anti-war movement, the women’s empowerment movement. What it did is it made all of us who were exposed to the art, we became Laser Focused man about what it is that we wanted and needed to do. Do your work, do your work wherever you can. If you have to start out in a community center… choreograph something and do it in a community center, if you got to a point where you needed a larger venue then start having conversations with people that work within some of those institutions. But first and foremost, you have to be driven to do work.

The obstacles are, are things that you create yourself, things which stop you from doing what you need to do. Now, yes, racism is real, separation is real. Preferential treatment is real. All of that stuff is real. At some point you have to make a decision to go for it.

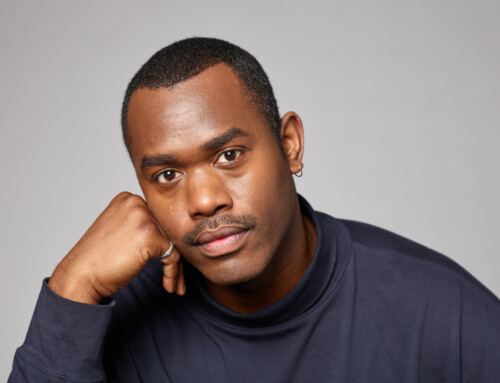

I don’t know if you know what’s going on in the dance world today, but there’s so many scandals about the treatment of dancers. Can you say a few words discipline with love ?

I would say … completely forthcoming …you know… that I have had a personality that evolved over the years. That the young choreographer Abdel, the insecure artist, the one who was searching for a voice, was not the same person that you, Armando, met in 2005. I had evolved. There is always some level of insecurity that we all have about things that we do. As you evolve and grow right, and you learn to look in the mirror, and you see the living strengths and also the living contradictions of yourself. You become less judgmental. I started, you know, seeing people with a greater degree of humility and a greater degree of grace, if you will.

I’ve worked my way through all of my bullshit, you know, that exists within, inside myself.

And I had become a person that was more nurturing, that was more loving, that was more caring. By then, I had a grown daughter, by the time you joined the company. So as you evolve, you want for your brother and your sister, what you want for yourself. I wanted the same kind of experience and love that I had, and I got some of that with my dance mother, Joan. And I got another part of it with Baba Chuck Davis. There you were, welcome. And, and even though I was critical as shit about something that I wanted to happen, I’ve always felt artistic. Even in my age, sometimes I succeed, and sometimes I don’t.

Photo from forcesofnature.org

What can we expect in this upcoming performance?

This performance, which is at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center Victoria Theater, is centered in the principles of empowering not only the African American community, but anybody that comes to it with inspiring them to live in accordance with the daily principles of unity. And the seven daily principles, you know, unity, self-determination, cooperative economics, collective work, responsibility, purpose, creativity and having faith. The work can be story driven, you know, or thematically driven. And so there are some ballets that we’re doing this year, that focus on community, economy, and the importance of meditation and prayer.

There is an African ballet called Sevens because of the seven principles and so it’s kind of abstract, and construct but it relates to the power of the number seven so all the rhythms are in seven all the movements are in meters of seven. Some of the casting is done in multiples of seven.

The other piece I said wall Street, 3.0, fallen Idols. And still is, in some cases, wall Street is an icon, you know, it’s held up, you know, as, almost as a staff at a symbol of worship and society. And, you know, and what happens when you exalt money a little too much.

There is also a piece about my mother’s life.

Can you quickly tell us what do you have coming up after this show? Where else can we see you?

Well, we have two school shows on December 20th.

We also have at the Apollo, our annual Kwanza celebration.

And then in January, I’m on the board of directors for the International Association of Blacks and Dance. We go to Memphis in to perform there.

We got a thing we’re doing on Ella and Duke at Aaron Davis at City College, in February.

And As you know I am the director of Dance Africa, That’s a big, huge thing.

Photo from forcesofnature.org

u04efc

весільний відеооператор рим

https://www.mymeetbook.com/budvacarscom

At me a similar situation. It is possible to discuss.

https://1x-bet-india.com