The idea for this column came from watching. Working as a dancer for Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, I spend a lot of time watching. In a company that is notorious amongst dancers for their specificity in details, I am trying to figure it out. It’s hard work. Of course. As is most work in dance and the arts. But so far in my career, it is here, in Wuppertal, that I have most had to face myself. Most had to ask questions that pierce a bit deeper into the flesh of performance communication.

What’s to it?

Does it really matter?

Are there differences? Can anyone tell?

Yes, Maybe.

For the premier post of ‘Seeking Magic’ I thought why not try to grasp the wriggling, ever-morphing being that is my experience, and see what insights she can offer. Before seeking outward, lets sit at this desk, on the schwebebahn, on this couch and ask.

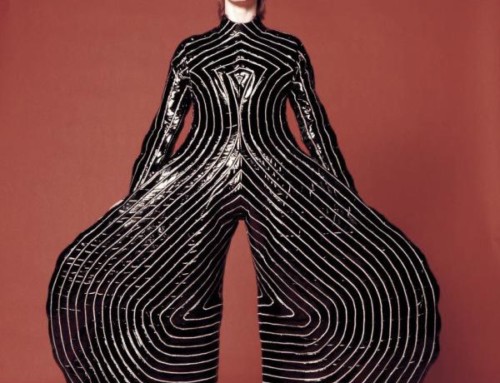

In mid October I had the opportunity and pleasure of receiving the role of Helena Pikon in “Der Fensterputzer” a piece by Pina Bausch. This is the first complete large role I would take over, and it is one with considerable challenges. For instance, opening the piece alone; scampering onto the stage, smiling charmingly in a short pink, child-like dress, hair decorated with an oversized bow (resembling a first prize ribbon given the winning horse at the Kentucky Derby) and addressing the audience from the heart in a high-pitched, crystalline voice, “Good Morning!”

Sounds easy, right? Fun maybe?

But it wasn’t. In trying this section, I quickly discovered it’s not just the action, it’s not repeating what I watched in the video, it isn’t enough. Why not? Why is speaking ‘good morning’ so difficult? It wasn’t the high-pitch that threw me (or the high-heels); I could feel the sparkle wasn’t there. The twinkle in the eye and the swell of the voice that can only stem from some organ some inches further down, was not happening.

So I took a step back. I watched Helena intently. I kept trying, while attempting to squeeze the key out of her. What was that twinkle?

I began to ask myself what it was that she was feeling. And then how could I translate that? But all of that is daunting, especially while still learning phrases and the role. So, another step back. Find an entrance, common ground.

Here, in the creation of pieces, form followed function. A question was asked, and the response created a form; an answer with the body of an emotion or state. This state for the performer could give viewers a feeling, a sense, something intimate, touching. Maybe something they too felt.

Now, those of us learning roles are in a way in the seat of the viewer. The tables have flipped. We have a form and are looking for the function.

This is how I found, find, am finding the empathy in the specificity.

As we work together, listening, doing, watching, repeating, it slowly reveals itself.

The specificity found and chiseled out, allows the form to loop back to the function. To find that feeling, one need place themselves in the form and the response is again there; honest and communicative.

So, this is where I find myself. Fixating on a form, trying to have it speak function to me. In the reteaching or passing on of these roles, it is our way. And these are minute details we are talking. The curve of the back, the exact moment of the high point of an arm, the rotation of the wrist…..

But through this work we can try to find empathy. Basic human emotions. And that branches out. The questions grow from, ‘what is she feeling; how can I translate that’ to ‘how does this person next to me feel that feeling?’ and ‘how can I share my translation with those watching? how will they know it as familiar?’ The form finds its greater purpose.

I remember in my audition for the company another woman asking what we should feel while performing a series of movements that repeated, diminishing in size, Lutz Förster answered something along the lines of, “you feel what you feel. What do you feel when you do these movements?” And I thought, ‘ah yes’, but at the same time, ‘wait, what?’

There is a balance to find. We must of course have context for the roles. There must be an idea of the scene, the pacing of the entire piece, what occurs before and after, anecdotes, etc. But once that is there, how do we really find what this original dancer was trying to answer to these questions?

Through form.

It is here that I realized how the specificity of form can open up empathy. Because of course I am another human being, another human body, but through the movement I tap into empathy. I can try to feel what it is that they felt, and more importantly how those feelings exist in me. In the dancer of 2015.

Breanna,

You state it so clearly and truthfully. Empathy. Specificity. But also Curiosity, which brought you to this. Thank you!

Thank you Stephen! I’m glad you enjoyed the post!

It was a leap to share these thoughts with the wide-web, but the response has proven that it is a worthy undertaking 🙂